A Golden Thread

Wine enters through the mouth and love the eye.

That’s all Yeats said we know —

but what we know comes through our noses.

The scent of truth: A golden thread we pull

loose from the tangle and follow

to its source. The universe unspins its heavy bobbin.

Consider this a koan.

Draw close enough to breathe its air.

—Matthew Kosinski

Each month we delve into a new story inspired by our scent of the month. This month Library takes us on a journey into the relationship between memory and scent.

Flash back, if it’s not too traumatizing, to your college years. It’s finals time, which means you’re hunkered down at a carrel in the university library for a marathon study session.

Earlier that day, back in your dorm room, you felt totally overwhelmed. Here, however, the daunting task of cramming for five exams feels downright doable.

It helps you’ve found a quiet spot where you can concentrate, but it’s not just the silence keeping you in the zone — it’s also the smellscape.

In your dorm, you contended with a less-than-invigorating bouquet of stale coffee and cold pizza, but the library is resplendent. The tang of ink, the slightly chocolatey scent of old pages, and the sweetness of the cherry wood desk form an aromatic cocoon around you, and you have no desire to leave it.

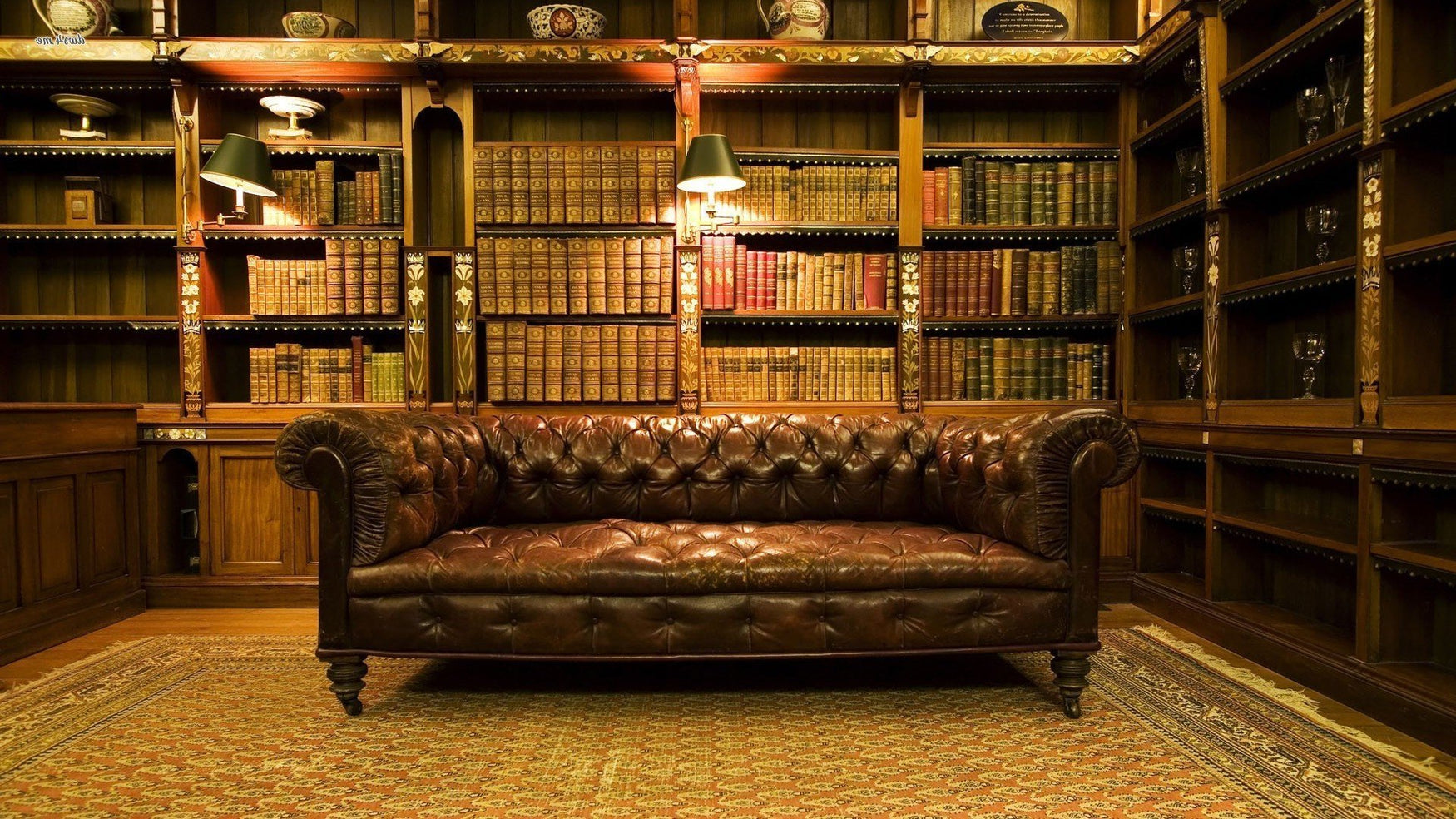

Librarys: a place of learning and specific scents. Credit: Sebastien Le Derout

But everything in the library — the carpet, the walls, even your fellow students — gives off a scent of its own. Why do you detect only a fraction of the library’s full range of smells? How, in this cacophony of odors, can you distinguish any one scent from another?

The answer is simple: You learned how to.

“Virtually everything around you gives off scent molecules. At any given time, you may be subject to hundreds or even thousands of smells.”

To Smell Is to Know

Smell is primal, like a reflex — isn’t it? A doctor bangs her little rubber hammer against your knee and your leg swings out; you walk into the kitchen and the scent of fresh bread fills your nostrils.

Not exactly.

A smell consists of a flurry of small molecules in the air around you. Those molecules hit your olfactory epithelium, a small patch of skin in the back of your nostrils, where they trigger your olfactory receptor cells. These cells send messages to your brain, and your brain registers those messages as a scent.

The cellular structure of the nose. Credit: Antranik

Virtually everything around you gives off scent molecules. At any given time, you may be subject to hundreds or even thousands of smells. All those competing scents could throw your whole olfactory system into disarray, but your brain has a trick. Using its previous experiences of other scents, it makes an educated guess about what you are currently smelling.

Thomas A. Cleland, a Cornell University professor who studies the psychology of scent, puts it this way: “You get this messy input, and the perceptual system in your brain tries to match it with what you know already, and based on what you expect the smell to be. So the system will suggest that the smell is X and will deliver inhibition back, making it more like X to see if it works. Then we think there are a few loops where it cleans up the signal to say, ‘Yes, we’re confident it’s X.’”

Like our eyes identifying illusory motion from this image, our noses are designed to identify patterns of olfactory signals as certain smells

The act of smelling is, itself, an act of learning, but scent and knowledge also relate to one another in a more immediately physical way. The olfactory bulb, which processes smells, connects directly to the hippocampus. When we learn some new bit of knowledge, it is the hippocampus that encodes the knowledge into our brain by creating new neurons and synapses. Aromas and new knowledge are processed in the same part of the brain.

In other words: Scent is literally the sense most closely linked with memory.

Follow Your Nose

“Oh strong-ridged and deeply hollowed / nose of mine! what will you not be smelling?” asks William Carlos Williams in his poem, “Smell!” “Must you taste everything? Must you know everything? / Must you have a part in everything?”

The answer seems to be “yes” — and that’s a good thing. A nose is more than just a sensory organ: It’s one of the most valuable instruments we have for decoding the world around us.

Every day, we navigate a world utterly suffused with scent. We can only distinguish one from another because our noses are constantly working, collaborating with our brains to identify the molecules that matter and filter out the rest.

William Carlos Williams captured the beauty of scent through poetry. Credit: The Guardian

The world of smell mirrors the world of everyday life. Amidst the roar of constant breaking news alerts, the buzzing and chirping of phone notifications, and escalating email inbox counts, it can feel downright impossible to focus on any one thing. How does a painter find space to practice his craft? How does a student shut out the noise and buckle down with her books? How can anyone learn anything at all when a tidal flood of information threatens to swallow us all whole?

To quote the world’s wisest cereal mascot: “Follow your nose.”

In addition to being linked with the hippocampus, the olfactory bulb also connects to the amygdala, which helps regulate our emotional states. Because of this connection, scent can affect our moods. Consider the comforting aroma of vanilla, or the way jasmine makes you feel almost drowsy. The right scents can put us in the mood to focus, which produces a headspace more conducive to learning.

Smell is connected with the emotional memory centers of the brain. Credit: Emory

In one study, the psychologist Mark Moss looked at the impact of scent on memory retention. One group of study participants took a memory test in a room infused with lavender, and another group took the test in a room infused with rosemary. A third group, the control group, took the test in a room infused with no scents. Those who smelled lavender did worse on the test than the control group, whereas those who smelled rosemary performed better. Moss found that those who smelled rosemary had elevated levels of the aromatic compound 1,8-cineole in their blood. 1,8-cineole is responsible for the minty scent of eucalyptus leaves — and it has also been shown to increase communication between brain cells, making it a particularly effective study aid.,

“The world will never sit quietly. It hums with energy and activity, but you don’t need to visit a library to keep it all at bay.”

Approaching the matter more metaphysically, Southern and Central American shamans often burn palo santo wood as incense. The incense is believed to ward off negative thoughts and energies, which can certainly get in the way of a good study session. Who hasn’t, after hearing some bad news, found it difficult to focus at work or school?

“[The scent of Palo Santo] kind of snaps you into attention, which is the point of ceremony and ritual — organizing your attention into yourself in the present moment,” acupuncturist Sandra Lanshin Chiu told lifestyle magazine Coveteur.

Even if your days of cramming for exams are behind you, there’s always something new to learn — and plenty to distract you from learning it. The world will never sit quietly. It hums with energy and activity, but you don’t need to visit a library to keep it all at bay. By simply sniffing a sprig of rosemary or lighting a Keap candle, you can create your own private library wherever you are.

—The Keap Team

Article Credits

Words by Matthew Kosinski

All credits noted.